Medina Lake and Canal System

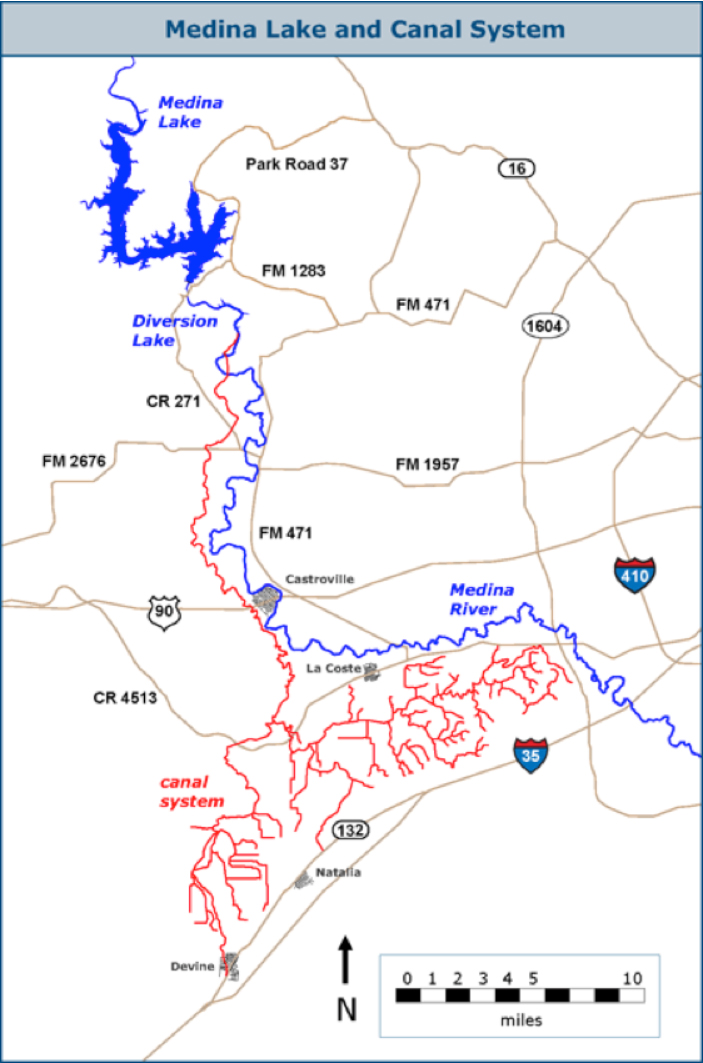

Medina Lake was constructed from 1911-1912 as an irrigation reservoir. An extensive canal system delivers water by gravity flow to 33,000 acres of irrigated farmland below the Balcones escarpment around Castroville, La Coste, Natalia, and Devine. Portions of the canal extend to urban San Antonio, just outside Loop 1604. At the time it was constructed, it was the biggest irrigation project west of the Mississippi. At spillway capacity, Medina Lake covers about 5,575 acres, has a length of 18 miles, a maximum width of three miles, 110 miles of shoreline, and a storage capacity of 254,823 acre-feet. BMA is authorized to impound 237,874 acre feet. In addition to the Medina Dam and Lake, Diversion Dam is about four miles downstream that creates Diversion Lake, from which discharges are made to the canal system.

Medina Dam, Medina Lake, and Diversion Lake were constructed partially on the Edwards limestone outcrop, so the lakes contribute large amounts of water to Aquifer recharge. Seepage losses from Medina Lake and Diversion Lake have been documented by the USGS and other sources since completion of the irrigation structures in 1912. All of the water lost from the lakes has been assumed to enter the Edwards Aquifer, either directly or indirectly through the Trinity Aquifer. In 2004, the United States Geological Survey completed a water budget analysis and concluded that an average of about 3,083 acre-feet recharges each month (Slattery and Miller, 2004).

In 1910, world famous engineer Dr. Fred Stark Pearson persuaded British investors to finance construction of the Medina dam and canal system. A crew of 1,500 men worked around the clock to mix 292,000 cubic yards of concrete and form it into a waterproof wall 164 feet high, 128 feet wide at the base, 25 feet wide at the top, and 1,580 feet long. Laborers received $2 a day, which were good wages for those days. Most were Mexican nationals who had prior experience building hydroelectric dams with Pearson in Mexico, and most of them brought their families. At least 70 people were killed by accidents and disease during the year of construction.

Although Dr. Pearson usually gets credit for building Medina Dam, it was not his idea, and several others were instrumental in the project. According to Rev. Cyril Kuehne, who published a historical account of the dam’s construction in 1966 called Ripples From Medina Lake, the original dreamer was Castroville founder Henri Castro. The year was around 1850, and means were not available, but Castro assured his fellow pioneers that someday a great dam would be build to harness the Medina River’s floodwaters and irrigate the land around Castroville. For decades, pioneers referred to the area that would become Medina Lake as the “Box Canyon”.

In 1894, Alex Y. Walton was on a hunting trip to the Box Canyon and, upon inspection of the natural contours, became convinced that waters could be held in readiness here and “according to the need for the service of man.” He sought expert advice, and obtained enthusiastic support from engineers Terrell Bartlett and Willis Ranney. After completing surveys and engineering plans, they enlisted the help of Judge Duval West to prepare all the legal papers that would be required.

Finally, all that was lacking was money, but for years the group was unable to interest anybody who could provide the capital. Discouraged but unwilling to give up, they turned to businessman Thomas B. Palfrey. He was not willing to finance the project himself, but he remembered that Dr. Pearson had employed his friend, a San Antonio native named Clint H. Kearny, and that Kearny had mentioned to him that water power and irrigation sites were becoming scarce in the world, and that if any good prospects were to come to his attention to be sure and let him know. Kearny visited the site and recommended it to Dr. Pearson, who, 16 years after Walton first visited the Box Canyon, finally succeeded in securing financing for construction from British investors.

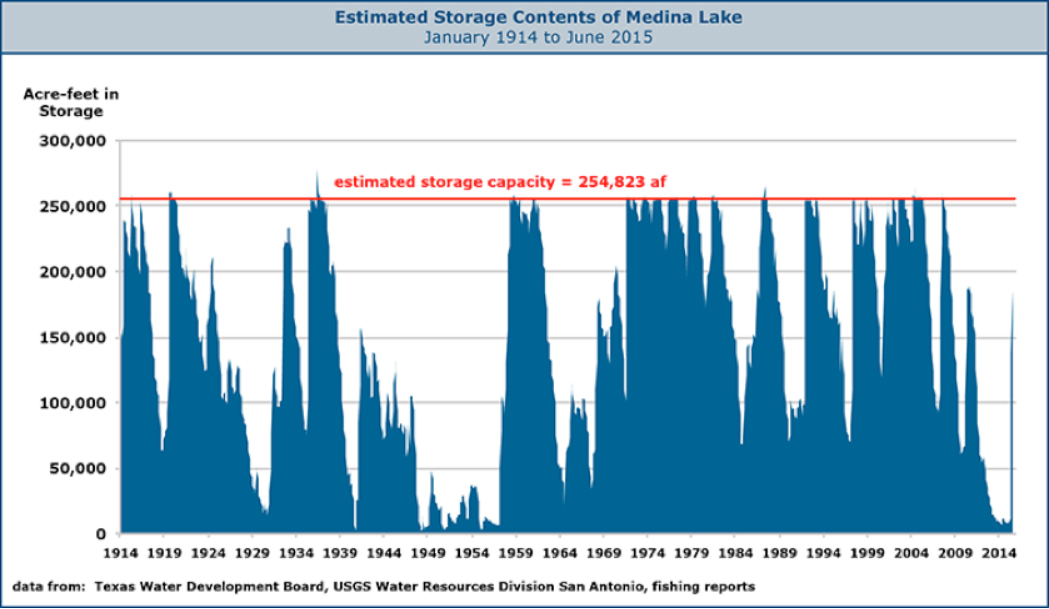

The pace of construction was frenetic, mostly because the builders expected large floods in the summer of 1913 that would fill the reservoir. The floods never materialized, and after construction was complete in November 1912, it was 18 months before any significant rains occurred. The Lake was not filled to capacity for the first time until September 1919. Whether the designers overestimated the rainfall or the size of the watershed is not clear, but what is certain is the Medina River watershed has simply never been able to supply as much water as they envisioned. Wildly fluctuating levels have characterized Medina Reservoir throughout its entire history.

Medina Dam was only one component of Alex Walton’s comprehensive master plan to establish town sites and sell land to prospective farmers. His group established the Medina Irrigation Company and laid out the town of Natalia, named after Pearson’s daughter Natalie. But before land sales could be started, world events spelled financial disaster for the project. When England became involved in World War I in 1914, Pearson’s access to British capital was limited, and the Company was placed in receivership. In order to make a personal appeal to British investors for more capital, Pearson and his wife boarded the Lusitania and perished when the ocean liner was torpedoed and sunk by a German submarine on May 7, 1915. After that, US federal courts did not allow any land sales, so the Company leased land until it was released from receivership. The stockholders preferred selling the Company to reorganizing, and there were several failed attempts to keep the endeavor alive, but all the subsequent corporations also went into receivership. Finally, in 1950, assets that had cost $6 million to build were sold for $10 and “other valuable considerations” to the Bexar-Medina-Atascosa Counties Water Improvement District No. 1 (BMA), which voters had established in 1925 to oversee the project. The BMA has continued to own and manage the project since that time.

The graph below estimates the contents of Medina Lake since it was first received significant inflow in 1914. There is uncertainty in the older numbers, and the newer numbers will change as new information becomes available.

Rains that have little effect on the Lake may reflect a new normal. In recent years, large areas of the Hill Country are becoming gentrified, with large ranches cut up into small residential ranchettes. Each new resident drills a new well, and many of them construct impoundments on tributaries of the Medina River to create private lakes. All of this appears to be impacting the volume of water that ends up in Medina Lake during smaller rainfall events.

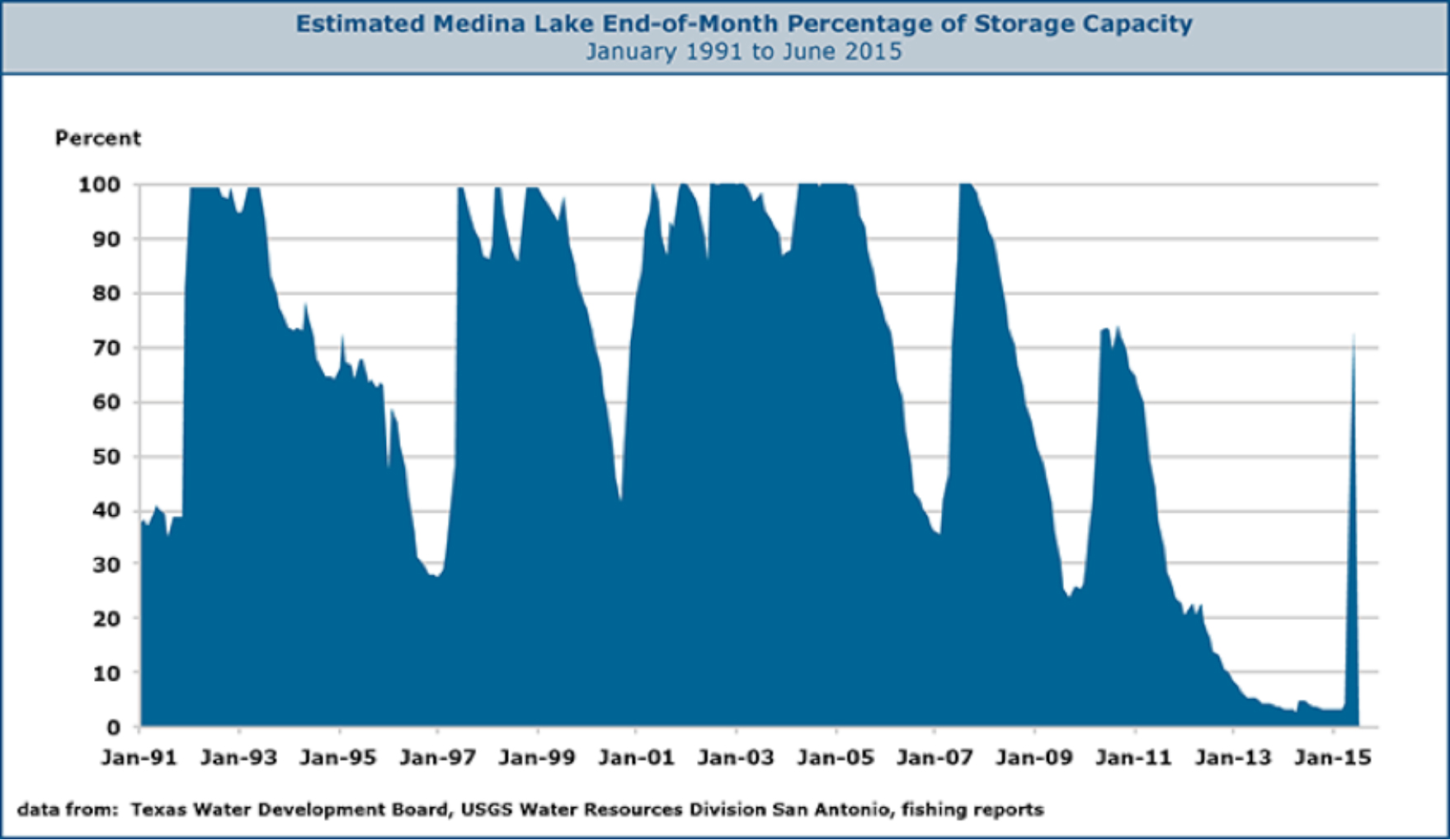

Here is a graph that shows estimated storage volume as a percentage of capacity since 1991. Generous rains fell over the region in 2012, but none of it fell above Medina Lake, so the lake continued to drop and finished 2013 at less than 4% of capacity. Rains in May and June of 2014 were above average, but they had little effect on the Lake.

In May of 2015, tremendous rains overwhelmed any of these new factors affecting inflow and the Lake gained almost 40% of its capacity in just one day, on May 24. It finished the month at 53% full. In June of 2015, the BMA resumed deliveries of water to irrigators. By the end of that month, it had recovered to almost 75% full.